CS09__Godsell FutureShack

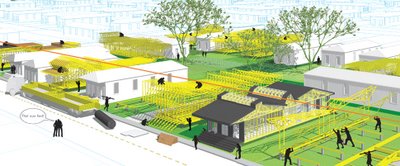

Originally submitted as part of the AFH Kosovo competition, Australian architect Sean Godsell put forth his own money to build the prototype FutureShack, a temporary housing solution for emergency relief situations.

The concept utilizes a non-descript shipping containing that is outfitted with a plywood interior that has been designed to accommodate the shelter’s program with built-in furniture, plumbing, and electrical components. A “parasol” roof is erected above the main structure to shade the structure and lessen any potential heat gains; it is said also that this roof structure is meant to begin to breathe life and a sense of home into the otherwise utilitarian design. The project also boasts of telescoping legs that are able to adapt to any presented terrain.

Sources:

architectureforhumanity.org/programs/kosovo/index.htm

samsung.com/Features/BrandCampaign/magazinedigitall/2005_spring/feat_02c.htm

www.archidose.org/Feb02/020402.html

www.seangodsell.com/

www.treehugger.com/files/2004/09/futureshack_by.php

[Image provided by www.treehugger.com.]